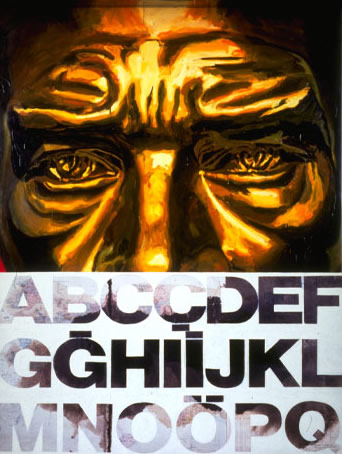

ATATÜRK/ALPHABET, 1991

ATATÜRK/ALPHABET, 1991 oil on canvas and acrylic on found map 226 x 175 x 7.5 cm

In his works entitled Sıfır/Cypher (1991), Atatürk-Alfabe [Atatürk-Alphabet] (1991) and Anıtkabir [Atatürk Mausoleum] (1990), Vahap Avşar represents ordinary visual objects, which some artists produce on request without any thought or any awareness in service of the military regime, perpetuating state myths, as they did in 1981, in unorthodox, skewed, and unexpected ways. It is a strange similarity that, here too, just as in socialist countries, the visual production of the state myth has been assigned to artists. On the other hand, one can see the same artists produce a type of art that is called “modern;” art that has no personality, has lost all its geographical orientation, and makes only anonymous references. In any case, “modern art” is the name given to a kind of second-hand duplication that is far removed from its place of birth, causes no unrest, makes no noise, and follows the current of middle-of-the-road European movements. Avşar’s recent work resists all these. He deals with the foundation myths of the Republic and the ways in which these are represented, but he is also au courant with the latest debates in art, having his answers to offer, and this concerns how he functions across different fields. The subject matter of an article I wrote years ago, one which preserves its urgency even today, was that the public monuments in Turkey, like the one in Taksim Square, are like a slap in the face from the powers that be for the people who, over the centuries, have seen none of the figures in their visual world as individuals, who have been unable to get used to such representations in the streets, and who cover the pictures in their homes with white muslin on holy days. The cover of a book entitled Güzelleşen Istanbul (1943), published when Lütfü Kırdar was the Mayor of Istanbul, depicts the Renaissance-style statue of İsmet İnönü, President at the time, looking majestic and powerful on horseback as he virtually tramples on the mosque that is photo-montaged onto the background. This has been the unique and coercive modernity of this place. Avşar’s painting questions the logic of this establishment, and addresses the ironic stance in the representation of Atatürk, the sloppiness of the production of his busts, the presentation of the myth in a banal form, and the bad copies and mass produced versions that increasingly depart from the “original,” creating a closed-circuit of internal references. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the factory that supplied the Soviet republics with mass-produced statues of Lenin in various forms and sizes had to stop production, and the factory yard became a dumping ground for Lenin statues due to a lack of demand. There used to be a workshop on the outskirts of Istanbul, right beside the E-5 highway, which produced Atatürk statues, with many samples in its yard – it may even still be there. It is usually under military regimes when bust and monument production increases. The monumental statues in Stalin’s Russia, in National Socialist Germany, and in former Bulgaria and Brazil are as ugly and banal as the ones in Turkey. Moreover, as we are strangers to the idea of a “city” and because the first time we came into contact with public monuments was 500 years en retard, the ones that do exist are tragically bad. Our society does not ask for statues in its squares, and thus there are no works that inspire urban pride. Atatürk’s portrait, as represented in Avşar’s painting, is borrowed from ordinary, cheap bronze Atatürk statues. Their resemblance to Atatürk is questionable; if an exhibition comprising of these statues were to be organized one day, the sloppiness with which they were Vahap Avşar, Atatürk-Alfabe [Atatürk-Alphabet], 1991 It was a time of conversation produced and the pathos of the situation would be exposed. Avşar’s Atatürk, consisting of two pieces, however, is painted in a painterly manner in opposition to the conceptual attitude of the process. It is painted with bold expressionist brushstrokes with occasional dripping. The second canvas carries the letters of the new Turkish alphabet that are placed against the background of the map of Turkey. The letters stop at “Q” – there is no such letter in the Turkish alphabet…

Vasif Kortun